When I lived near Marquette Park, there was a lot of racial tension. The neighborhood suffered from panic as the blacks moved closer and closer due to white flight. When my mother bought our house at 2509 W. Marquette Road, the neighbors said, with a sigh of relief, “At least you’re not black.” But we weren’t completely accepted by many in the neighborhood.

No matter where you lived in Chicago back in the 1970s, there would be someone who resented you, regardless of your race. In 1966, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had marched in Marquette Park was greeted by whites who threw bricks, rocks, and bottles at the marchers. We moved to Marquette Park in 1973 and people still talked about the Doctor King march. I was a typical teenager in that I wasn’t fully aware about the political events in Chicago or our neighborhood.

So, one Saturday in 1975, I was driving home from work at Derby Foods. When I got close to my house, all the streets were blocked off by the police and I couldn’t drive home. Helicopters flew overhead. I drove around until I found a side street that wasn’t closed. I managed to park my Firebird about four blocks from my house. I had no idea why there were so many police officers in our neighborhood, nor why all the streets were closed.

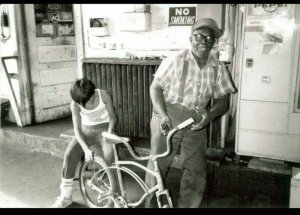

As I walked home, I could hear people chanting in the direction of my house. When I reached Marquette Road, there were hundreds, if not thousands, of people lining both sides of the street. Reverend Jesse Jackson had led a protest march, but I had just missed it. The street was littered with rocks and bottles. A black man and a boy drove up Marquette Road and people threw rocks and bottles at his car shouting racial epithets. The car sped off westbound where he was greeted by more projectiles.

I had a tough time crossing Marquette Road to get home. When I finally got to my house, there were hundreds of people standing in front of my house. I couldn’t reach my front door, so I watched until the march was over and most of the people left. My younger brother told me how he saw police officers on horses near California Avenue. Someone blew up a cherry bomb near the horse and scared it so that it stood on its hind legs. Someone kicked one of horse’s hind legs and the horse and police officer both fell. The police immediately arrested the offender.

One of my friends told me he was standing on the curb watching all the action when a little old white lady gave him a brick and said, “You throw it! I’m too old!”

When I finally got home, my mother asked me where I was. I told her that I was at work and that I had a hard time getting home. When my mother asked my brother if he was at the march he swore he was at his friend’s house. My mother didn’t believe him. She didn’t want the neighbors to think we were causing trouble. Little did she realize that all our neighbors were out there throwing things. The next day, my mother punished my brother for being at the march and for lying to her. She had seen my brother on the news near where the horse was kicked down. They had more protest marches after that, but that was the only one I saw up close.