Mexicanas are incredibly unique women in this world. However, I don’t want to lump them all into one group as there are different kinds of Mexicanas. Sure, they all have the common denominator of Mexico somewhere in their background and that’s enough to differentiate them from women of other ethnicities. So in an effort to educate you, gentle reader, I will over-analyze Mexicanas for you. Yes, there are different kinds of Mexicanas that I like to divide into three groups: 1. Mexicanas, 2. Mexicanas, and 3. Mexicanas. As you can see, UIC didn’t give me my Ph.D. for nuthin’! I learned to categorize just about everything while studying for my graduate degrees. Anyway, if you examine my groups of Mexicanas, you will clearly see that there are three different kinds of Mexicanas: 1, 2, and 3. Is that clear?

First, there are Mexicanas like my abuelita, born and raised in Mexico, destined never to live anywhere else. And they don’t want to leave Mexico either. Their names are usually María or Guadalupe. Or even Guadalupe María or María Guadalupe. No exceptions. My abuelita María Guadalupe Valdivía came to Chicago only because my mother insisted. Abuelita didn’t like Chicago at all because it wasn’t Mexico. She hated the winters here and she hated the fact that she would have to learn English. She stayed just long enough to have her eye surgery and then she returned to Mexico. And she never came back. And she never missed Chicago at all. My mother would visit abuelita at least once a year in Mexico. And even though she was blind, abuelita lived by herself in Mexico. She was an extraordinarily strong Mexicana.

Second, there are Mexicanas like my strong-willed mother who were also born and raised in Mexico, but not firmly rooted there. They come to America for a while, then go back to Mexico. But return to America even though they always complained about America in Mexico. They just keep going back and forth, never entirely happy in either place. In general, nothing seems to please them. My mother always complained about everything, to everyone in America and Mexico. When her Mexicana friends would visit, they would all sit around complaining about America. And then, to change the subject just a little, they would complain about Mexico. Nothing ever seemed to please these Mexicanas as they sat around complaining and breast-feeding their babies.

Third, there are Mexicanas like my sister or ex-wives, born in America, but unmistakably Mexicana by their accent. I once had a Mexicana girlfriend who had the Mexicana accent but couldn’t speak a word of Spanish! She used to get so mad when people automatically spoke Spanish to her and she would have to admit that she only knew English, albeit the Mexicana kind of English. These Mexicanas love everything about Mexico, the music, the food, the culture, but they wouldn’t want to live there. It’s okay to visit once in a while to catch up with family events, but that’s about it. America is their home, even if they are Mexicanas, and they never hesitate to let the gringos know it.

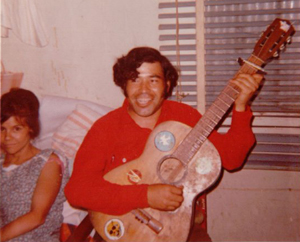

I’ve known Mexicanas all my life, beginning with my mother, then my abuelita, and finally, my significant others. The more I get to know them, the less I seem to understand them. I do know they are sexual beings from observing them and from my very own personal hands-on experience. I don’t know much about my abuelita’s sex life, but let me say this. She never married my abuelito and they rarely lived together. Yet they managed to have six children together. My parents were always fighting, and I never ever heard them having a normal, civilized conversation. My father was always affectionate with my mother, but she would repel all his amorous overtures, at least that I could see. Occasionally, when my father didn’t work the midnight shift, I could hear him trying to seduce my mother in their bedroom, right next to mine. My father always saying something affectionate and my mother always telling him to leave her alone. Apparently, he didn’t give up and she didn’t resist enough because they had six children together. My youngest brother was born soon after my parents separated.

The Mexicanas that came into my life were certainly very affectionate, if you know what I mean. That’s the thing about Mexicanas: They immediately know if they like you or not, if they will love you or not. I met my first wife Linda when my friend invited me to go with him to a wedding in Merrill, Michigan. We barely spoke and I didn’t see her again for another month–and we spoke even less then. Next thing I knew she moved to Chicago just to be with me–not that I minded, of course.

My second wife Anna chased after me, too. She kept hinting for me to ask her out. I really wasn’t interested in her, but she was persistent. She gave me her phone number and I threw it away. Her friend gave me Anna’s phone number and I threw it away again. She was so persistent that I finally gave in. If a Mexicana is that interested in me, I know we will be happy together. If Mexicanas don’t love you, or at least like you, you better back off because you don’t have a chance and you’re just wasting your time.

From what I’ve seen, the odds are against you if you think you can win a Mexicana over. However, once she yours, you better show her that you need her, and she’ll be yours for as long as she wants you. But that may or may not be till death do you part. One of the fringe benefits of having a Mexicana is having an active sex life. I mean there’s no begging at all. In fact, I was dragged into the bedroom many times, although I must admit that I didn’t put up much of a fight. And the fun doesn’t stop just because it’s that time of month, either. In fact, a Mexicana wants you even more right then. This happened to me many times. And just because you have all these intense arguments during the day, doesn’t mean that you’ll be ignored at night. In fact, that’s usually some of the best lovemaking. And the next morning? She continues being mad at you from the day before. That is, until night falls again.

Well, that’s about all I’m willing to say for my over-analysis of Mexicanas for now. But someday, I’ll truly delve into Mexicanas to try to understand them! Maybe, I’ll discover that there are many more than just three groups of Mexicanas.