My youngest brother Joseph’s name should have started with the letter D.

J should have been D. But he wasn’t. He was J. And for an incredibly good reason. My mother said so!

Well, I’ve already talked about my mother’s naming process in my previous blog entries. My parents had six children: David Diego, Daniel, Diego Gerardo, Dick Martin, Delia Guadalupe, and Joseph Luis. All of names started with D–except for Joseph (which starts with J and not D, as I’m sure you probably noticed. I have always admired the intelligence of my readers!).

The other notable oddity in the naming process is Daniel who has no middle name! I was less than two years old when Daniel was born, so I have no idea why he has no middle name. Were we too poor to afford a middle name for Daniel? Was my mother mad at my father for getting her pregnant again and so she denied my father Diego yet again the opportunity of having a son named Diego? I really don’t know because neither my father nor mother ever talked about how Daniel got his name. To this day, Daniel’s lack of a middle name remains one of the great mysteries of our family.

Before my youngest brother Joseph Luis was born, my parents were in the middle of a hostile separation and later a contentious divorce. How my mother got pregnant was a mystery to me even back then because I hardly ever saw them together for about a year. But somehow, she got pregnant. And my father was proud of the fact that he had gotten her pregnant.

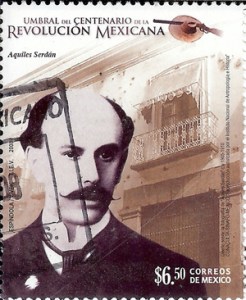

However, there was never any doubt that Joseph was my father’s son because when Joseph was older, many people thought he and I were twins. The resemblance was that strong. So how did he come to be named Joseph Luis? Well, he was born in August of 1968, days after our Uncle Joseph, my father’s much younger brother, died in Viet Nam.

I remember when my Uncle Placido called to say he had to visit us to tell us something particularly important. He came after my brothers and I were already in bed, so I knew he had something important to say. I listened from my bedroom, which was right next to the kitchen where they sat. I heard my Uncle Placido say that my Uncle Joseph had died in Viet Nam. I could hear both my mother and father crying. I cried, too, in my bedroom. So, my mother named my brother Joseph in his memory. That was actually an incredibly good reason not to follow the D rule in naming us.

Our Uncle Joseph was everyone’s favorite uncle. He loved playing with all his nephews and nieces. Everyone cried when he died. It was the longest funeral procession I had ever seen–and I lived by a funeral home, so I saw a lot of funeral processions!

My father was one of his pall bearers. The day after the funeral, my father couldn’t get up out of bed. He was paralyzed from the waist down. Whether his paralysis was physical or psychosomatic was never determined, not even by the doctor who came to our house to treat my father. After about a week, my father just got up out of bed and started walking again. He wanted to go to work again.