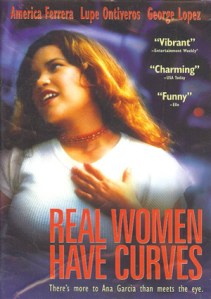

I really loved the movie Real Women Have Curves (2005, Directed by Patricia Cardoso) even though I’m not a woman and I’m not from Los Angeles. I laughed throughout the movie because I could identify with the Mexicans who were portrayed accurately in the movie. We could see the importance of family unity and how going to college could be perceived as a threat to this unity. Education is not viewed as a positive goal in a Mexican family that has relied on manual labor to survive. Carmen (Lupe Ontiveros) wants her daughter Ana (America Ferrera, as of late as Ugly Betty on TV) to work in her sister Estela’s dress shop instead of going away to college.

Ana finally gives in to her mother’s wishes, but you can see that Ana is not only unhappy there, but she really does not belong there because she has so much more potential than that of a laborer. But that’s how Mexicans think sometimes. Even though Carmen complains about how hard she has worked as seamstress throughout her life, she is willing to subject her daughter to the same punishment of manual labor.

Carmen also criticizes her daughter about her excessive weight, even though Carmen herself is overweight. However, beauty is in the eye of the beholder and Ana is beautiful in her own way. Her boyfriend Jimmy tells her that she’s beautiful and he seems genuinely sincere when he compliments Ana.

If she were in Mexico, many men would consider her beautiful simply because she has a nice smile, a nice personality, and is pleasingly plump. Once when I was in Mexico, my cousin saw a pleasingly plump woman and he flirted with her by saying, “Oye, esa gordita viene con atole?” Well, if you don’t know Spanish, I better explain that in this context gordita means both pleasingly plump with positive connotations and also refers to a food that is made of corn flour stuffed with chicken or beef; atole is a tasty, hot drink made from corn. I guess this sentence doesn’t translate well, so I’ll give you a similar example in English. Suppose an attractive woman, say dressed seductively in a short skirt, struts her stuff past you, jiggling all her assets, my cousin could say something like, “Does that shake come with fries?”

This difference in beauty standards reminds me of a story that Rosie O’Donnell once told on a talk show–I believe it was Johnny Carson’s–before she was really famous. She talked about how she went to Mexico with a thin, beautiful Hollywood actress, which at the time I wondered why she would go to Mexico with another actress. Well, now that she’s famous and I know a little more about her personal life, I know why she went to Mexico with a thin, beautiful Hollywood actress. Anyway, Rosie and her thin “friend” were at a bar where all the men were hovering around Rosie instead of her friend. Finally, Rosie asked one of the Mexican men why they found Rosie more attractive than the beautiful actress. One of the men said, and you must imagine Rosie saying this with a Mexican accent, “The bones are for the dogs. The meat is for the men!”

Well, this movie really got me to think about my mother again, whose name also happens to be Carmen. My mother never valued education and there was absolutely no possibility of college in my future. She always told me that I would work in a factory when I was old enough to work. But she would always complain about how factory work was wearing her down. She always came home sore and tired from working.

One day, she showed me her swollen hands and said, “Someday you’ll see what it’s like to work hard. One of these days you’ll be working in a factory just like me.” I didn’t plan to ever work in a factory, so I told her, “That’s why I’m going to college!” She said, “Why are you going to college if you’re only going to work in a factory?” She couldn’t imagine any other occupation for me.

She eventually found me a factory job–a job that would have been ideal for my mother, but not for me because I had such higher aspirations. However, since I lived under her roof, I had to live by her rules, so I began working the midnight shift in a peanut butter factory two days before my eighteenth birthday, while I was still a high school junior. I really hated this job! When I got out of work at 7:00 a.m., I immediately had to get ready to go to school even though I was ready to go to bed.

I was always tired in school and often fell asleep during my afternoon classes. I told my mother that I couldn’t work full-time and go to school full-time. She told me that if I didn’t work, I couldn’t live with her; I would have to move in with my father, which she had always described as being my worst possible destiny. So, I continued working at the factory, but when I couldn’t take the stress of working and going to school anymore, I dropped out of high school. My mother didn’t complain because I was still working, and I was contributing to the family financially.

In the movie, Ana gets accepted to Columbia University with a scholarship, but her parents are against Ana leaving the family in order to study in New York City. Her father finally gives his blessing to Ana, but Carmen doesn’t even say goodbye to Ana when she leaves for school. Carmen merely watches from her bedroom window. But you can see that not all Mexicans value education as much as most Americans who know the importance of going to college to get ahead in life.

When you consider this anti-education attitude of Mexicans in general, you can see why they have a high school drop-out rate of about 50%. At least the movie ends on a positive note with Ana going off to Columbia University and we get to see her walking the streets of NYC near Times Square.