Good Friday always reminds me of many things. I know, I know, it’s Saturday. I’m not late. I’m running on Mexican Time. I once saw that on a T-shirt.

If you ever have a party and invite some Mexicans, make accommodations for Mexican Time. If you want everyone to be at your house by four, tell them the party’s at three. Well, because 3:00 o’clock lasts until 3:59! 3:59 is still 3:00 in the mind of a Mexican. Say 3:59 out loud. Go ahead. Did you hear all three digits? If you did, you’re not Mexican. A Mexican will only hear the initial digit “3” and then block out the rest of the digits. That’s just how Mexicans process time.

Anyway, I forgot all about Good Friday until late last night when Jay Leno mentioned that it was Good Friday. And then I felt guilty. Because I’m a lapsed Catholic who suffers from constant guilt. It’s like being Mexican. You never stop being Catholic–or feeling guilty about something. Well, during the day yesterday, I remembered that it was Good Friday. I thought I should celebrate it in my own lapsed-Catholic fashion to ease some guilt for forgetting about not going to church on Good Friday. So, I had decided to write a blog entry about Good Friday. But then I forgot all about it. Or I blocked it out. And now I feel extremely guilty. That’s why I’m writing this while Good Friday is less than twenty-four hours over. I feel a little less guilty now.

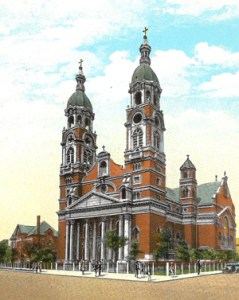

As Mexican Catholics, we attended a Lithuanian Catholic church in the Back of the Yards. Holy Cross Church was our parish. I also attended Holy Cross School from kindergarten through eighth grade. There was no separation between church and school. We were taught lessons in church, and we prayed in school. In church, we were taught by Lithuanian priests and in school Lithuanian nuns taught us, with the occasional visit by the pastor who would give us holy cards if we answered his catechism questions correctly. We never forgot about religious holidays because we were in school five days a week and in church six days a week. We would be reminded for weeks in advance of an upcoming holy day. Holy Week was one of the most important times of the year for us. It began on Palm Sunday and ended on Easter Sunday.

Mexicans in Chicago commemorate many of these events by reenacting them. I’ve been to reenactments of the Last Supper, Jesus Christ’s procession to Golgotha, and the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ. This always struck many people, who were of the non-Mexican persuasion, as sacrilegious.

To this day, the holy day that I remember the most is Good Friday. That was the day that Jesus Christ was crucified for our sins. And we should never forget that!

We attended school on Good Friday until it was time to go next door to church for the Good Friday service at 3:00 p.m. sharp. All the students sat with their classmates and nuns who were their teachers. We would get to church early so we could pray until the service began. We were supposed to recall all the events of Jesus Christ’s life and how he died for our sins.

I remember when I was about eight years old, the nun told us in school that Jesus Christ died at three p.m. and that every Good Friday it rains at that time for Jesus Christ. I was just a boy and I believed absolutely everything I was taught. During the Good Friday service, the bright sunny church interior suddenly dimmed and then darkened. Just as the priest told of how the Romans were nailing Jesus Christ to the cross, the church became as dark as night. Someone turned some lights on. Then, we saw lightning flashes and a moment later we heard deafening thunder. The church trembled and the lights flickered. The thunderstorm, lightning, and thunder continued for several minutes. The priest stopped to genuflect and bless himself. That was a defining moment in my development as a young Catholic. I became a true believer at that precise moment. From then on, I always believed everything that the priests and nuns told me.